Sample-Based Krylov Quantum Diagonalization (SKQD)¶

Sample-Based Krylov Quantum Diagonalization (SKQD) is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that combines the theoretical guarantees of Krylov Quantum Diagonalization (KQD) with the practical efficiency of sample-based methods. Instead of expensive quantum measurements to compute Hamiltonian matrix elements, SKQD samples from quantum states to construct a computational subspace, then diagonalizes the Hamiltonian within that subspace classically.

Why SKQD?¶

Traditional quantum algorithms like VQE face several fundamental challenges:

Optimization complexity: VQE requires optimizing many variational parameters in a high-dimensional, non-convex landscape

Measurement overhead: Computing expectation values \(\langle\psi(\theta)|H|\psi(\theta)\rangle\) requires many measurements for each Pauli term

Barren plateaus: Optimization landscapes can become exponentially flat, making gradient-based optimization ineffective

Parameter initialization: Poor initial parameters can lead to local minima far from the global optimum

SKQD addresses these fundamental limitations:

✅ No optimization required: Uses deterministic quantum time evolution instead of variational circuits

✅ Provable convergence: Theoretical guarantees based on the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle

✅ Measurement efficient: Only requires computational basis measurements (Z-basis), the most natural measurement on quantum hardware

✅ Noise resilient: Can filter out problematic measurement outcomes and handle finite sampling

✅ Systematic improvement: Increasing Krylov dimension monotonically improves ground state estimates

✅ Hardware friendly: Time evolution circuits are more amenable to near-term quantum devices than deep variational ansätze

Understanding Krylov Subspaces¶

What is a Krylov Subspace?¶

A Krylov subspace \(\mathcal{K}^r\) of dimension \(r\) is the space spanned by vectors obtained by repeatedly applying an operator \(A\) to a reference vector \(|\psi\rangle\):

The SKQD Algorithm¶

The key insight of SKQD is that we can: 1. Generate Krylov states \(U^k|\psi\rangle\) using quantum time evolution 2. Sample from these states to get computational basis measurements 3. Combine all samples to form a computational subspace 4. Diagonalize the Hamiltonian within this subspace classically

This approach is much more efficient than computing matrix elements via quantum measurements!

[1]:

import cudaq

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import cupy as cp

import numpy as np

from skqd_src.pre_and_postprocessing import *

use_gpu = True #this is for postprocessing, the quantum circuit simulation is done on GPU via the nvidia target using CUDA-Q

if use_gpu == True:

from cupyx.scipy.sparse import csr_matrix

from cupyx.scipy.sparse.linalg import eigsh

else:

from scipy.sparse import csr_matrix

from scipy.sparse.linalg import eigsh

cudaq.set_target('nvidia')

cudaq.set_random_seed(42)

np.random.seed(43)

cp.random.seed(44)

Problem Setup: 22-Qubit Heisenberg Model¶

We’ll demonstrate SKQD on a 1D Heisenberg spin chain with 22 qubits:

[2]:

num_spins = 22

if num_spins >= 63:

raise ValueError(f"Vectorized implementation of postprocessing supports max 62 qubits due to int64 packing. Requested: {num_spins}")

shots = 100_000

total_time_evolution = np.pi

num_trotter_steps = 8

dt = total_time_evolution / num_trotter_steps

max_k = 12 # largest k for U^k

eigenvalue_solver_options = {"k": 2, "which": "SA"} # Find 2 smallest eigenvalues

Jx, Jy, Jz = 1.0, 1.0, 1.0

h_x, h_y, h_z = np.ones(num_spins), np.ones(num_spins), np.ones(num_spins)

H = create_heisenberg_hamiltonian(num_spins, Jx, Jy, Jz, h_x, h_y, h_z)

exact_ground_state_energy = -38.272304 # Computed via exact diagonalization

hamiltonian_coefficients, pauli_words = extract_coeffs_and_paulis(H)

hamiltonian_coefficients_numpy = np.array(hamiltonian_coefficients)

Krylov State Generation via Repeated Evolution¶

For SKQD, we generate the Krylov sequence:

where \(U = e^{-iHT}\) is approximated via Trotter decomposition.

Implementation Strategy: 1. Start with reference state \(|\psi_0\rangle\) 2. Apply Trotter-decomposed time evolution \(k\) times for \(U^k|\psi_0\rangle\) 3. Measure each Krylov state in computational basis 4. Accumulate measurement statistics across all Krylov powers

[3]:

@cudaq.kernel

def quantum_krylov_evolution_circuit(

num_qubits: int,

krylov_power: int,

trotter_steps: int,

dt: float,

H_pauli_words: list[cudaq.pauli_word],

H_coeffs: list[float]):

"""

Generate Krylov states via repeated time evolution.

Args:

num_qubits: Number of qubits in the system

krylov_power: Power k for computing U^k|ψ⟩

trotter_steps: Number of Trotter steps for each U application

dt: Time step for Trotter decomposition

H_pauli_words: Pauli decomposition of Hamiltonian

H_coeffs: Coefficients for each Pauli term

Returns:

Measurement results in computational basis

"""

qubits = cudaq.qvector(num_qubits)

#Prepare Néel state as reference |010101...⟩

for qubit_index in range(num_qubits):

if qubit_index % 2 == 0:

x(qubits[qubit_index])

for _ in range(krylov_power): #applies U^k where U = exp(-iHT)

for _ in range(trotter_steps): #applies exp(-iHT)

for i in range(len(H_coeffs)): #applies exp(-iHdt)

exp_pauli( -1 * H_coeffs[i] * dt, qubits, H_pauli_words[i]) #applies exp(-ihdt)

mz(qubits)

Quantum Measurements and Sampling¶

The Sampling Process¶

For each krylov power $ = 0, 1, 2, \ldots, k-1$: 1. Prepare the state \(U^k|\psi\rangle\) using our quantum circuit 2. Measure in the computational basis many times 3. Collect the resulting bitstring counts

The key insight: these measurement outcomes give us a statistical representation of each Krylov state, which we can then use to construct our computational subspace classically.

[4]:

all_measurement_results = []

for krylov_power in range(max_k):

print(f"Generating Krylov state U^{krylov_power}...")

sampling_result = cudaq.sample(

quantum_krylov_evolution_circuit,

num_spins,

krylov_power,

num_trotter_steps,

dt,

pauli_words,

hamiltonian_coefficients,

shots_count=shots)

all_measurement_results.append(dict(sampling_result.items()))

cumulative_results = calculate_cumulative_results(all_measurement_results)

Generating Krylov state U^0...

Generating Krylov state U^1...

Generating Krylov state U^2...

Generating Krylov state U^3...

Generating Krylov state U^4...

Generating Krylov state U^5...

Generating Krylov state U^6...

Generating Krylov state U^7...

Generating Krylov state U^8...

Generating Krylov state U^9...

Generating Krylov state U^10...

Generating Krylov state U^11...

Classical Post-Processing and Diagonalization¶

Now comes the classical part of SKQD: we use our quantum measurement data to construct and diagonalize the Hamiltonian within each Krylov subspace.

Extract basis states from measurement counts

Project Hamiltonian onto the computational subspace spanned by these states

Diagonalize the projected Hamiltonian classically

Extract ground state energy estimate

The SKQD Algorithm: Matrix Construction Details¶

The core of SKQD is constructing the effective Hamiltonian matrix within the computational subspace:

Computational Subspace Formation: From quantum measurements, we obtain a set of computational basis states \(\{|s_1\rangle, |s_2\rangle, \ldots, |s_d\rangle\}\) that spans our approximation to the Krylov subspace.

Matrix Element Computation: For each Pauli term \(P_k\) in the Hamiltonian with coefficient \(h_k\):

\[H = \sum_k h_k P_k\]We compute matrix elements: \(\langle s_i | P_k | s_j \rangle\) by applying the Pauli string \(P_k\) to each basis state \(|s_j\rangle\).

Effective Hamiltonian: The projected Hamiltonian becomes:

\[H_{\text{eff}}[i,j] = \sum_k h_k \langle s_i | P_k | s_j \rangle\]

[5]:

energies = []

for k in range(1, max_k):

cumulative_subspace_results = cumulative_results[k]

basis_states = get_basis_states_as_array(cumulative_subspace_results, num_spins)

subspace_dimension = len(cumulative_subspace_results)

assert len(cumulative_subspace_results) == basis_states.shape[0]

# matrix_rows, matrix_cols, matrix_elements = projected_hamiltonian(basis_states, pauli_words, hamiltonian_coefficients_numpy, verbose) #slower non-vectorized implementation

#if use_gpu is True, the projected hamiltonian & eigenvalue solver are computed on the GPU

matrix_rows, matrix_cols, matrix_elements = vectorized_projected_hamiltonian(basis_states, pauli_words, hamiltonian_coefficients_numpy, use_gpu)

projected_hamiltonian = csr_matrix((matrix_elements, (matrix_rows, matrix_cols)), shape=(subspace_dimension, subspace_dimension))

eigenvalue = eigsh(projected_hamiltonian, return_eigenvectors=False, **eigenvalue_solver_options)

energies.append(np.min(eigenvalue).item())

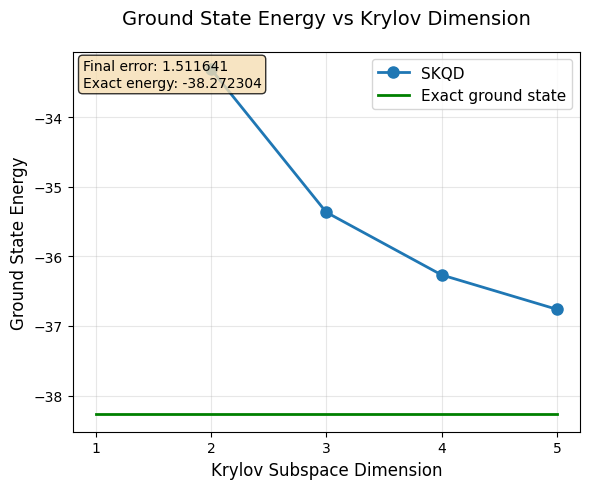

Results Analysis and Convergence¶

Let’s visualize our results and analyze how SKQD converges to the true ground state energy. This is the moment of truth - does our quantum-classical hybrid algorithm work?

What to Expect:¶

Monotonic improvement: Each additional Krylov dimension should give a better (lower) energy estimate

Convergence: The estimates should approach the exact ground state energy

Diminishing returns: Later Krylov dimensions provide smaller improvements

The exact ground state energy for our selected Hamiltonian was computed earlier via classical exact diagonalization and will be used as the reference for comparison with SKQD results.

[6]:

# Create visualization of SKQD convergence

plt.figure(figsize=(5, 4))

all_dims = range(1, max_k)

plt.plot(all_dims, energies, 'o-', linewidth=2, markersize=8, label='SKQD')

plt.plot(all_dims, [exact_ground_state_energy] * (max_k-1), 'g', linewidth=2, label='Exact ground state')

plt.xticks(all_dims)

plt.xlabel("Krylov Subspace Dimension", fontsize=12)

plt.ylabel("Ground State Energy", fontsize=12)

plt.title("Ground State Energy vs Krylov Dimension", fontsize=14, pad=20)

plt.legend(fontsize=11)

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

final_error = abs(energies[-1] - exact_ground_state_energy)

plt.text(0.02, 0.98, f'Final error: {final_error:.6f}\nExact energy: {exact_ground_state_energy:.6f}',

transform=plt.gca().transAxes, verticalalignment='top',

bbox=dict(boxstyle='round', facecolor='wheat', alpha=0.8))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

GPU Acceleration for Postprocessing¶

The critical postprocessing operations are:

Hamiltonian projection onto computational subspace

matrix_rows, matrix_cols, matrix_elements = vectorized_projected_hamiltonian(basis_states, pauli_words, hamiltonian_coefficients_numpy, use_gpu)

Sparse matrix construction

projected_hamiltonian = csr_matrix((matrix_elements, (matrix_rows, matrix_cols)), shape=(subspace_dimension, subspace_dimension))

Eigenvalue computation

eigenvalue = eigsh(projected_hamiltonian, return_eigenvectors=False, **eigenvalue_solver_options)

This substantial acceleration comes from: - Parallel Pauli string evaluation across thousands of basis states simultaneously - Vectorized matrix element computation leveraging CUDA cores - GPU-optimized sparse linear algebra via cuSPARSE library for eigenvalue solving

The speedup becomes increasingly critical as the Krylov dimension grows, since the computational subspace dimension (and thus the matrix size) scales exponentially with k. For higher k values, GPU acceleration transforms previously intractable postprocessing into feasible computation times.

Note: Set use_gpu = True at the beginning of the notebook to enable GPU acceleration for postprocessing. The quantum circuit simulation uses the NVIDIA target in CUDA-Q regardless of this flag.

The data in the plot below was gathered by averaging over 5 runs on a NVIDIA H100 GPU and an Intel Xeon Platinum 8480CL CPU with 224 threads. The only thing that changed between the 2 data points was use_gpu = True and use_gpu = False.

[7]:

print("Using:", cudaq.__version__)

Using: CUDA-Q Version (https://github.com/NVIDIA/cuda-quantum 37053302ceb3d83684186b2a99aac500df7b847e)